The Gates Mausoleum (not Bill Gates, who is very much alive) in the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx is a massive display of wealth. Robert “Bet-a-Million” Warne Gates, who made a fortune manufacturing and selling barbed wire and founding an oil company that later became known as Texaco, and had a penchant for gambling, built the austere classic revival-style light-gray granite mausoleum. The mausoleum is of the Doric order—characterized by the fluted columns with no base resting directly on the stylobate, the capitals are slightly curved and unadorned. The architrave (stone panel that traces around the building just above the column) is plain, as is the frieze which is generally enhanced with triglyphs, guttae, and bas-reliefs. The cornice (the triangle-shaped architectural element above the door) is plain and adds to the solemnity of the tomb.

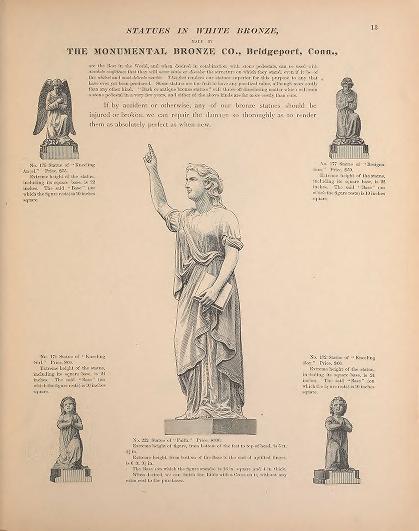

The massive bronze door into the mausoleum’s interior was created by the famed sculptor, Robert Ingersoll Aitken in 1914. Many great artist’s works can be found in North American cemeteries, including those sculpted by Daniel Chester French, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Aldabert Volck, Felix Weihs de Weldon, Karl Bitter, Martin Milmore, Alexander Milne Calder, T. M. Brady, Albin Polasek, Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, William Wetmore Story, Edward V. Valentine, Nellie Walker, Lorado Taft, Sally James Farnham, Adolph Alexander Weinman, Solon Borglum, and John Gutzon Borglum, a veritable who’s who in the art world. These artists were able to earn a living creating sculptures, public and private. Aitken “was a California-born sculptor who had trained in Paris and taught at the National Academy in New York.” Aitken’s most well-known work are the nine sculptures that adorn the pediment on the Supreme Court Building in the U.S. Capital in Washington D.C.

The mourning figure on the door of the grand mausoleum is described in the book, Sylvan Cemetery: Architecture Art & Landscape at Woodlawn, as a “flowing figure of a grieving woman, seen from the rear with drapery slipping down to revel a long and sinuous form, a play of curved and angular contour lines. Her long fingers speak of the tension between her continuing agony at her loved one’s absence, as seen in the clawing motion of her right hand and her need for calm reflection and endurance in the left hand. Her head is bowed and her face hidden from our view signifying the ravages of grief works on the harmony and beauty of the human face.”

Robert Ingersoll Aitken (1878 – 1949) also created a sculpture of a seated angel sculpture as a funerary monument for William August Starke in the Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The bronze sculpture is 69 inches high and 62 inches wide, resting on a light rose-colored unpolished granite base that is 44 inches high, 63 inches wide and 53 inches deep.

The angel has Calla lilies laying in her lap, recognized as a symbol of marriage. Aitken completed the monument in 1921—signed in the lower left corner of the bronze plinth, “AITKEN FECIT”—Latin for “Aitken made it.”

William A. Starke, a Milwaukee businessman and entrepreneur, was an immigrant, who along with his four brothers, came to the States from Kolenfeld, Germany. The five brothers founded the C. H. Starke Bridge and Dock Company, were involved in the Milwaukee Bridge Company, the Christopher Steamship Company, and the Sheriff Manufacturing Company.

William Starke was married to Louise Manegold Starke (1858 – 1939) who is buried next to him, as well as their 40-year old daughter, Meta Eleanor Starke Kieckhefer (1883 – 1923).

T

T