HUSBAND

CHARLES A. HAGGERTY

BORN AUG. 2, 1870

KILLED IN WOODS RUN WRECK

APRIL 5, 1897

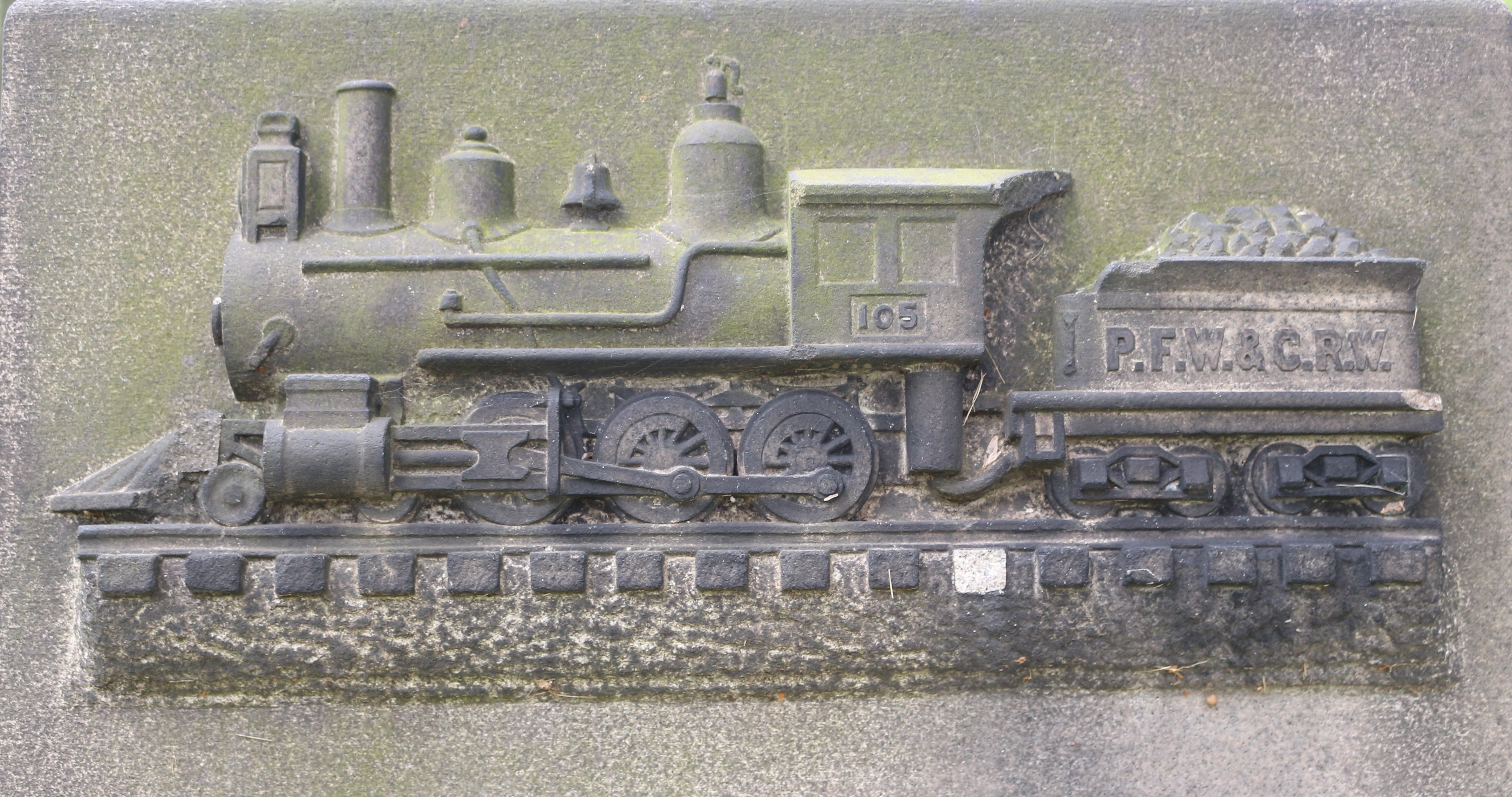

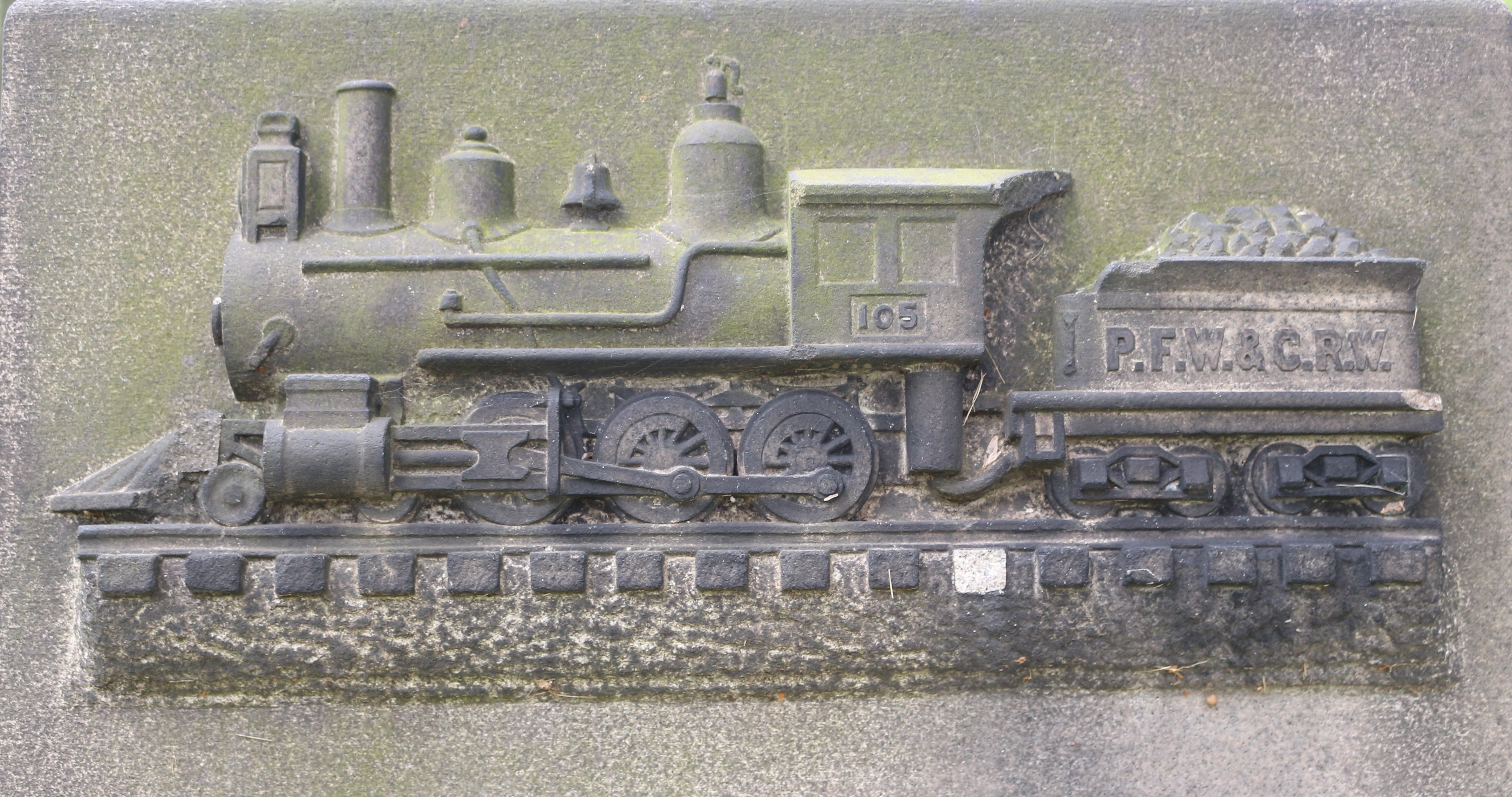

The small square-top tablet in the Union Dale Cemetery in Pittsburgh displays a bas-relief of a locomotive at the top of the gravestone—not just any engine, but the likeness of the Pittsburgh Fort Wayne & Cleveland Run Woods that killed Charles Haggerty in a trestle span collapse. The Monday, April 5, 1897 Pittsburg Press printed the following headlines:

“THE SPAN GAVE WAY.

Coal Train Wrecked at Ohio River Connecting Bridge.

FIREMAN HAGGERTY WAS KILLED.

AND ENGINEER GRAHAM RECEIVED

INJURIES THAT WILL BE FATAL.

THE TRAIN FELL 75 FEET.”

The following excerpt of the article on the front page of the evening Pittsburgh Press published the dramatic details of the accident:

“The Employees Were Buried Under the Cars and Coal-McClure Avenue Was Completely Obstructed. The Accident Caused Great Excitement in Lower Allegheny.

“A span of the Ohio Connecting railway bridge, over McClure avenue, Allegheny, gave way about 6:15 this morning, and a mixed freight trin which was crossing together with the engine, were precipitated to the street, fully 40 feet below. The causalities were:

“CHARLES HAGGERTY, Fireman, killed.

“WILLIAM GRAHAM, engineer, fatally hurt. Body badly mangled; now at St. John’s hospital.

“The train pulled out from the panhandle yards on the south bank of the Ohio, bound for the Ft. Wayne road. It passed over the river in safety, but when about midway of the McClure avenue span the trestle gave way and the engine and 13 cars plunged to the street below. Engineer Graham and Fireman Haggerty went down with the engine and were buried in the wreck. The cars and coal were scattered in every direction completely bocking the street. In addition to the coal cars, two cars containing structural iron were also piled in the wreck.

The engine, tender and one car passed over McClure avenue in safety. The third car was of the hopper description and was loaded with coal. When it was directly above McClure avenue, the street span collapsed, fully 100 feet of the structure giving way. The heavy weight pulled the engine, the tender and the first car back, and precipitated them into the street below. Car after car followed, until the street was filled to the level of the trestle above.

In the fall the engine turned completely over. Graham and Haggerty were unable to jump and were caught in the falling train. West-bound passenger train 101 on the Fort Wayne road, and east-bound train #42 on the Cleveland & Pittsburg road were passing when the bridge collapsed. Both were compelled to stop. It was by the east-bound train that the news of the disaster was first brought to Allegheny. The wrecking trains of the Fort Wayne and Cleveland & Pittsburg roads were at once dispatched to the wreck. Word was also sent to the Allegheny central police station and No. 3 patrol wagon and eight officers were sent to assist the wrecking crews.

Work was at once commenced upon the lower end of the wreck, in order that the imprisoned engineer and fireman might be rescued. Superintendent A. B. Starr, and other officials, arrived early at the scene of the accident, and at once assumed the management of the men engaged in the rescue. The steam dome of the big engine was broken by the fall and the escaping steam permeated every part of the wreck.

Almost 200 men were put to work with shovels, crowbars and saws, and shortly after 7 o’clock the cab of over-turned engine was reached. Haggerty was found dead upon the cab floor, an iron bar having fallen upon the prostrate body, and cut it in twain. The remains were carried out and the search continued for Graham. The escaping steam and scalding water made it almost impossible to work but the wrecking crew continued bravely and shortly before 7:00 Graham was found crushed beneath the engine tender. He was still alive, but the flesh was badly burned about the upper part of the body. Considerable difficulty was experienced in getting the injured man from the wreck. It was finally accomplished, and he was sent to St. John’s hospital. The remains of Haggerty were taken to Thomas Payton’s undertaking room on McClure avenue…”