Gravely Speaking and Syngrammata have decided to dig deep into our photo collections in order to bring you pairs of images drawn from our many years combing through American cemeteries. Each pair will be linked by a theme which we are free to interpret. Suggestions of future themes to follow are welcome in the comments! This week’s theme is: the most unusual gravestone, fitting for Halloween.

Gravely Speaking writes:

Indiana limestone is abundant in the state. Some of the most flawless limestone can be found in a rich trough between Bedford and Bloomington referred to as Salem limestone. The Pentagon, the soaring National Cathedral and the solemn Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., New York City’s Empire State Building, the Biltmore Mansion is Ashville, North Carolina, and 35 of the 50 state capitol buildings were built with Indiana limestone. It is a beautiful, rich cream-colored stone that is fairly easy to work. Generations of talented carvers learned their craft in this state, and it continues to be a place of gifted and creative carvers.

Not only can the stone carvers’ talents be seen in spectacular buildings but even in modest tombstones across the state. Indiana has thousands of tree-stump tombstones that dot cemeteries through the entire state and exported throughout the country. The carvers have also created one-off works of art. One such marker, photographed by my friend and neighbor, Doug Parker, is the tombstone of Charles Jacob Affelder in the Chesterton Cemetery in Chesterton, Indiana, in the Northwest corner of the state.

The tombstone has a figure that some people on various Web sites refer to as a Gollum-like creature from Tolkien’s The Hobbit, crouching under a gothic roof. The bare-chested man has his right hand resting on the top of a ham radio and his other hand is clutching a microphone. Carved on the front of the tombstone is, “Charles Jacob Affelder, N3AYU.” The tombstone is a curious sight, in an otherwise average Midwestern cemetery.

Further investigation of the deceased Affelder reveals that he was born August 5, 1915, in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. He was an avid ham radio enthusiast. The mix of letters and numbers, A3AYU, listed underneath his name was his ham radio callsign. Affelder had been a ham operator since 1933. He held several patents for improvements to the radio microphone, perhaps memorialized in stone on his marker. Affelder also worked for KDKA in Pittsburgh and for the Voice of America behind the scenes as an engineer. Affelder’s tombstone is a tribute to his love of the radio world to which he dedicated so much of his life and career. Charles Jacob Affelder died on January 10, 1994, at Chesterton, Porter County, Indiana.

Syngrammata writes,

In the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C., Thomas Mann has created for himself a monument in the form of a library’s catalog card, little paper cards that were used in olden tymes to allow library users to find books and do research. They were secured in long little drawers by metal rods that went through a hole in the bottom of each card. An elegant cataloging method for a more civilized age, these cards held a sophisticated series of symbols and texts arranged in standardized ways in order to convey crucial bibliographical information as efficiently as possible.

Mann’s monument reveals a lot about his professional interests as one of the librarians of Congress. His endgame is good, too: where better for a librarian of Congress to end up than the Congressional Cemetery?

Mann gives his name and birth year at the top: Mann, Thomas, 1948-; then comes his profession, Librarian. He was “published” in Chicago by parents Charles H. and Margaret Mann, in 1948. The Revised editions came out in Baton Rouge, 1976, and Washington, DC, 1980. Perhaps these marked turning points in his life, like the births of children; perhaps these mark his moving to Baton Rouge to pursue the Master of Library Science degree from Louisiana State University, and his subsequent move to Washington, D.C., where he took up employment at the Library of Congress in 1981.

He advises us of a Future corrected edition in the hands of a Higher Editor, an inside joke referring to Benjamin Franklin’s epitaph:

“The Body of B. Franklin, Printer;

Like the Cover of an old Book,

Its Contents torn out,

And stript of its Lettering and Gilding,

Lies here, Food for Worms.

But the Work shall not be lost;

For it will (as he believ’d) appear once more,

In a new and more perfect Edition,

Corrected and amended

By the Author.”

Returning to Mann’s stone, he has the conventional subject headings section, which on his stone read: 1. Christian. 2. The lack of a subject header number 2 seems to me to indicate that being a Christian was (after library science, perhaps) his first and defining identity.

The symbols in the bottom third of the stone pose the stubbornest challenges. Z710 .M23 is a section and cutter number within the Library of Congress catalog. Z710 is where to find “bibliographies, reference works, and materials related to library science”: precisely Mann’s professional area. Within Z710 the cutter .M23 specifies books on these topics by . . . Thomas Mann! His well-received final book, the 2015 Oxford Guide to Library Research, 4th edition, has the Library of Congress call number Z710 .M23 2015. Put another way, the code Z710 .M23 is a unique proxy for Thomas Mann, his name, if you will, in the specialized argot of library science. Under that code we fittingly find Library of Congress.

025.5’24 perplexed me, but it turns out to be the Dewey Decimal System code for Mann’s above-mentioned Oxford Guide. The Dewey number would normally be written 025.5/24. The final numerical string is 0221-1948. This resolves itself pretty quickly into a date, 02 (February) 21 1948, which is listed at one site as Mann’s birthday.

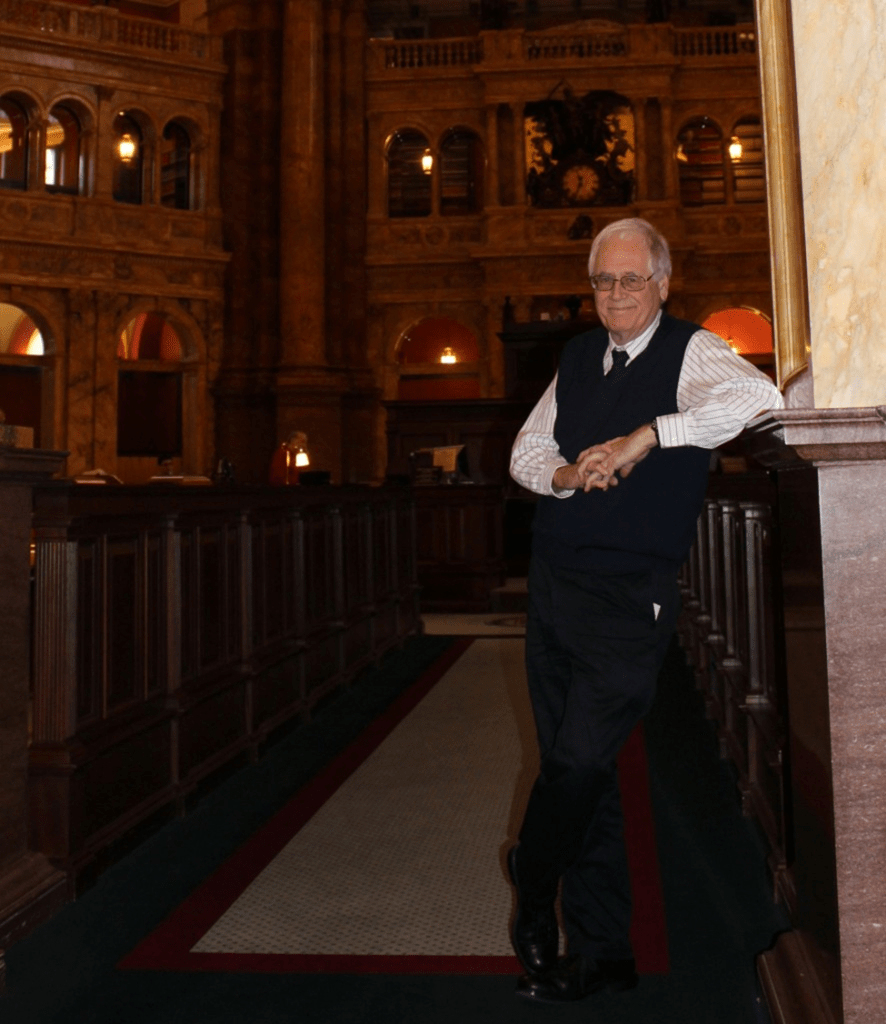

AARC 2 stands for Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, second edition, which codifies the conventions for determining how information is structured and recorded. MARC, by contrast, stands for Machine-Readable Coding. It’s a standard governing the digital registration of bibliographic and cataloging information to make sure that one computer can talk to another about this data. Nicely tying it all together is the typewriter font, since in said olden tymes these cards were all manually typed out. The Mann himself: